I recently participated in a panel debate at the NPD DisplaySearch US FPD conference on the future of the smartphone and tablet, considering which, if either was more likely to drive greater market disruption moving forward. My inclination was to back the sure thing: the smartphone has already disrupted so many surrounding technologies and I see no reason why it will slow down any time soon. Consider this, according to the Connected Intelligence SmartMeter (on-device metering), the average smartphone user does something on their smartphones 110 times per day. Think about that - once every nine or ten minutes we reach out for out phone (assuming a good night’s sleep is had).

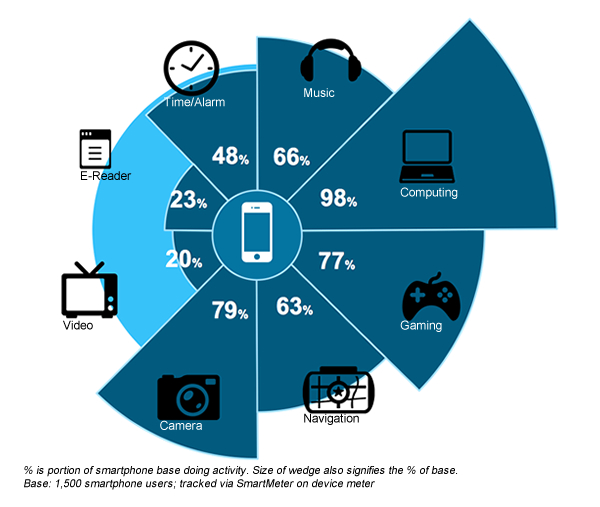

As a result, it’s clear that the smartphone is the device of choice for most of us and has disrupted not just surrounding technologies, but the very fabric of how we exist. The below graphic highlights just some of the disruption to date, looking at how we use the smartphone for activities that used to be the sole domain of alternative products, such as personal navigation devices (remember those?).

To be clear, the smartphone has not necessarily subsumed all related activity. Take, for example the PC: just because we use the smartphone for PC-related activity such as email, web browsing, and social network updates, doesn’t mean we don’t also need a PC. According to the Connected Home Report, 97 percent of Internet households still actively use the PC. After all, not all PC-related activities are easy to complete on a phone or tablet, today. But in other instances, such as music and navigation, the smartphone has had a fundamental impact on the “legacy” devices.

It is clear that a disruptive product’s job is never done, and I suspect the smartphone has plenty more innovation to come. One clear target is the TV environment. On the chart above, video adoption looks artificially low with only 20 percent of the smartphone base leveraging video, and it is. To make the point, I’ve stripped out all of the free video, such as YouTube or Vevo, which would drive the usage numbers sky-high. Instead, I’ve focused on the money, looking only at subscription-based video, such as Netflix or Hulu Plus. Twenty percent of smartphone users at least dabble in subscription-based viewing on their phone once a month or more.

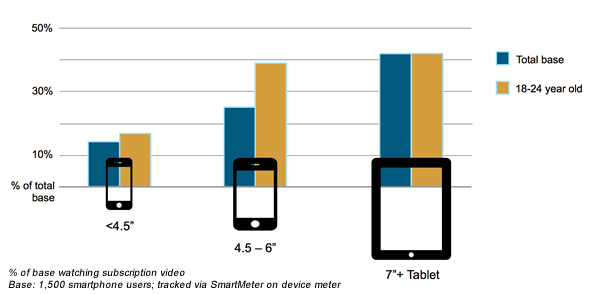

And size does matters and impacts the adoption of subscription video. Once the screen size is greater than 4.5 inches, adoption increases, and the bigger the screen, the greater the adoption, scaling up to the tablet-sized 7 inch screen. And if we look at a younger audience, adoption is boosted once again, with 4.5 to 6 inch screened smartphones commanding almost as many users as a tablet.

Does this place the TV under threat? Obviously not, but it does provide another core audience for streaming video services. What we are beginning to see is the potential for video services to be pulled through the smartphone, rather than via a set-top box or connected TV. Further, as screen-sharing solutions, such as Chromecast, increase in popularity, the smartphone-centric user has the opportunity to “throw” their streaming content to whichever screen is the most convenient, be it the large flat-screen in the living room or remaining on the 6 inch screen while traveling. As with nearly all other smartphone disruptions, the genesis for this is the drive for “my” content on “my device”, rather than a shared environment. Welcome to Generation Me. For traditional content providers such as TV networks, the lesson from this is loud and clear: more emphasis must be placed on developing strong app solutions to target this younger audience now.

There is, of course, the argument that this younger audience, rather than driving change will themselves change, evolving into a more sharing, caring generation as they start families. I’m not convinced. Evolve? Yes, but to hope that they will follow the same path is foolish. I suspect that content will remain an individual focus, rather than a shared environment. This is not to say we won’t still see TV family nights and so on, but these can still be driven from a smartphone or tablet.

Which brings us to the original debate as to which device will drive greater disruption and I have a simple, if perhaps cheating answer. Simply put, both will cause disruption because fundamentally the tablet and the smartphone are fast-becoming one and the same. Smartphones are getting larger while tablets are getting smaller. The only technical difference these days is that tablets, at least in the U.S. market, do not support cellular-based voice. So what? The younger generation hardly uses that anymore, choosing instead data-focused solutions such as Facetime and Skype.