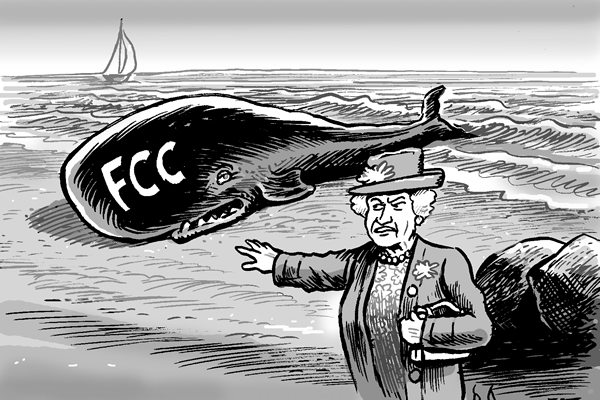

In England, all beached whales must be offered to the Reigning Monarch. This law came into force in 1322, is still in effect today and is, of course, a rather silly law in today’s world. No policy maker would consider building a proposal based on the precedent set out in the 1322 law. And yet, I feel that the FCC has used similar logic to argue that the Internet is not a telecommunications network, leveraging decisions from as long as 50 years ago, which is probably the equivalent of 1322 in “computer years.” The FCC’s argument is, if the Internet is not a telecommunications network then it is no longer under the jurisdiction of the FCC, and hence “net neutrality” disappears in a puff of questionable logic.

But to define the Internet as an “information service” is simply incorrect. At its core, the Internet is a telecommunications network, designed to send data of any kind. This could indeed be information services, via the Web, or could be data packets of video, video chats and even voice calls. The bottom line is that everything sent over a network today is “data” whereas 50 years ago there was a far clearer distinction between voice – the dominant communications mode at the time – and the nascent data network needs.

The FCC’s argument is convenient, though. It allows the Commission to step away from Net Neutrality without having to explain in too much detail quite why it believes that the previous policy was wrong; but, this move is deeply flawed on several counts.

Firstly, there is the assumption that any carrier flaunting the underlying principles of Net Neutrality will be abandoned by consumers, who are now, “empower[ed] …to choose the broadband Internet access service that best fits their needs.” This assumes that there are multiple broadband options for consumers, but in many regions of the U.S., this simply is not the case. Indeed, in parallel with this latest move, the FCC is also reducing the need to support more rural customers with high-speed options, suggesting that mobile, or alternative slower speed solutions, are adequate. This sets the stage for a carrier – an Internet Service Provider (ISP) – to define the pricing, tiers of service, and throttling and/or prioritization any way they choose.

And about that throttling or prioritization, which is truly at the heart of the Net Neutrality principal. Many of the broadband carriers now own content services and can use the lack of neutrality as a way to tip the scales of balance against competitors. This could range from prioritizing their own content services ahead of others (for example, a cable company could prioritize the cable-associated version of a channel’s app, and lower the throughput of a cord-cutting equivalent). Or, the carrier (ISP) could provide zero-rated data (i.e., when the carrier doesn’t count the use of a specific app against the data limit the consumer may have) for certain video services over mobile or fixed broadband, while still charging for other, competitive services. That could lead to consumer behavior where they are empowered to pick the free data content over ultimately more expensive alternatives. Heck, the lack of neutrality could even be something as basic as forcing you to have a homepage that is owned by the carrier, which means that they can have better leverage over ad revenue, search solutions and the initial news that you see.

These types of examples make the content providers, ranging from giants such as Facebook and Google, down to much smaller companies, very nervous about the lack of neutrality, as well as explain the division between carriers – who mostly have objected to Net Neutrality – and the content providers who clearly benefit from a more level playing field. To the content providers, equal access to – and for – consumers means they can compete on having a better product, rather than having a fatter wallet to pay for premium access. In other words, the very innovation that created the explosion of the Internet in the first place risks being stymied through a lack of regulation.

Even writing that line feels wrong. Growing up, as I did, in a country full of inconsistencies and strange laws (it’s also illegal to be drunk in a pub in the UK – think about that!) taught me that less regulation is often a good thing. But in this case, I truly believe that the FCC got it right in the first place by imposing the Neutrality mandate. Of course, perhaps the most ironic thing about the proposed change is what it potentially means for the FCC itself over time. If the Commission’s argument is valid, and the Internet (particularly the first mile from the home, whether that is fixed or mobile) is no longer something that the FCC (remembering that the “C” stands for communications) should have within its mandate; one has to wonder what is left? Perhaps, as a result of this move, the FCC is soon going to be a beached whale itself. And my guess is, the Queen probably has no interest in this particular whale.